Innate Immune Response

The innate immune response, also known as the non-specific immune response, is the first line of defense against pathogens. Its purpose is to prevent the movement of pathogens into and throughout the body. It is known as the non-specific immune response as it generally blocks non-self pathogens (a bacteria, virus, or microorganism that can harm the body) instead of being specific to a particular pathogen.

The innate immune response is immediate and occurs over the course of 96 hours depending on where the pathogen enters the body. Important cells that serve a purpose in this immune response are natural killer cells (a white blood cell that has small particles with enzymes that can kill infected cells), macrophages (large cells that engulf and destroy target cells, bacteria, and other large pathogens), and neutrophils (white blood cell that heals tissues and infections) (monocytes and granulocytes above). Other important immune cells are the dendritic cells (Langerhans on the diagram is a type of dendritic cell, antigen-presenting cell), mast cells (responsible for immediate allergic reactions), basophils (white blood cell, also allergy-associated), and eosinophils (white blood cell, commonly seen with allergies, parasitic infections, and cancer)(granulocytes above). The innate immune response senses pathogens and their products but doesn’t require antigen presentation (see below). All these cells can initiate inflammatory reactions at the site of infection or damage.

Adaptive Immune Response

The adaptive immune response, also known as specific immunity or acquired immunity, comes after the innate immune response. Adaptive immune responses are specific to a particular pathogen. Critical cells in the adaptive immune response, the T cell and B cell, are antigen-specific.

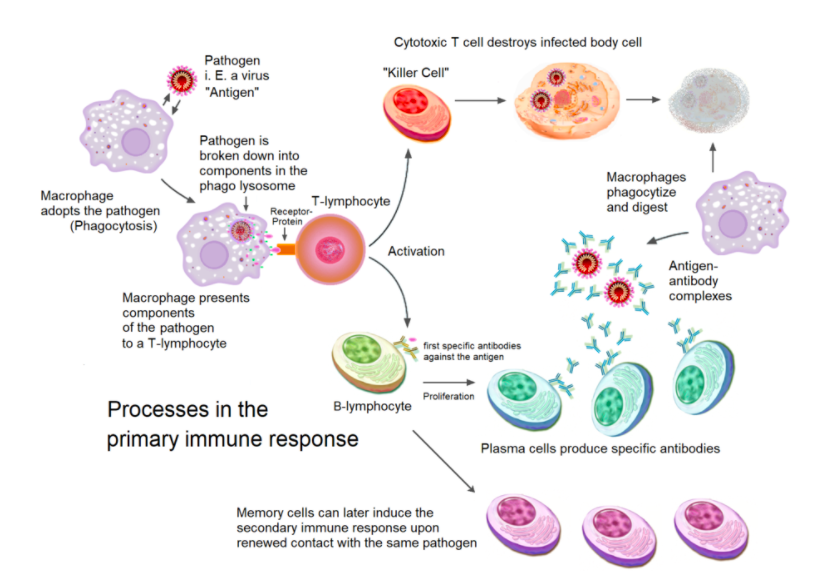

The adaptive immune response is a long-term response, with the peak occurring at 10-14 days. The primary cells involved in the adaptive immune response are the dendritic cells, T lymphocytes, and B lymphocytes. It is necessary for there to be an antigen present for the T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes to become activated effector cells.

The dendritic cell (DC) engulfs the pathogen, breaks it down with lysosomal enzymes, takes fragments of the pathogen’s proteins (antigen), and presents it on its cell surface using the major histocompatibility complex class type II (MHC class II). Next, a naive T cell (a T cell that hasn’t bound to an antigen yet) binds to the antigen on the DC. The DC also has on its surface co-stimulatory molecules, which bind their corresponding binding partners on the surface of the T cell to jumpstart the activation process. Cytokines secreted by the DC and other innate cells in the local tissue environment determine T-cell polarization. Certain cytokines induce up-regulation of transcription factors that make the T-cell differentiate into either Th1 (helper T-cell 1) or Th2 cells (helper T-cell 2). The now activated (effector) Th cell then releases cytokines that help speed up its own proliferation and activation and goes on to activate pathogen-specific B cells.

T cells are classified into two subtypes, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells. CD4+ T cells (also known as Helper T cells or cells) are the T cells that release cytokines to orchestrate the immune response. These cells bind to the MHC class II (see below) with the CD4 co-stimulatory molecule. CD8+ T cells kill specific target cells directly and can target any cell and bind to MHC class I. MHC class I are cell surface recognition elements expressed on all cells of the human body. MHC class I are molecules that present peptides in the cell and signal the cell’s physical state to effector cells (T lymphocytes and natural killer cells). The CD8+ T cells form pores in the target infected cell and allow enzymes into the cell that makes the cell commit apoptosis (cell death).

The other major adaptive cell type, the B cell, expresses pathogen-specific antibodies on its cell surface and can also secrete them into circulation. Once activated by a Th cell, the B cell proliferates, secretes antibodies, and also differentiates into both memory B cells and plasmablasts. Memory B cells remain in circulation and can produce more plasma cells if needed and secrete antibodies that fight against the pathogen. Plasma B cells circulate in the bloodstream and release antibodies; these cells normally only live for about two weeks.

After the immune response has been conducted the helper T-cells and macrophages will cease to release pro-inflammatory cytokines to the site of where the pathogen was and the body will return back to its normal, non-inflamed state.

Definitions:

Antibodies: A blood protein that counteracts a specific antigen. Antibodies combine chemically with substances that the body recognizes as foreign.

Antigen: Any substance that causes your immune system to produce antibodies against it

Basophils: Least common white blood cell type, made in bone marrow

CD4+ T cells: They activate the cells of the innate immune system, B-lymphocytes, cytotoxic T cells, as well as nonimmune cells, and also help suppress immune reactions

CD8+ T cells: A subpopulation of MHC class I-restricted T cell and are mediators of adaptive immunity. Included cytotoxic T cells, which are important for killing cancerous or virally infected cells, and CD8-positive suppressor T cells, which restrain certain types of immune response

Cytokines: small proteins that have an effect on other cells

Dendritic cells (DCs): Antigen-presenting cells (APC) in the immune system. Their main function is to process the antigen and present part of it on the cell surface to show the T cells of the immune system. They act as messengers between the innate and the adaptive immune systems

Effector T cells: T-cells that have been encountered their specific antigen and are now activated. Includes several T cell types that actively respond to a stimulus like CD4+ and CD8+

Langerhans cells: tissue-resident dendritic cells of the skin, present in all layers of the epidermis

Macrophages: Large, specialized cells that recognize, engulf, and destroy target cells

MHC class I molecule: major histocompatibility complex, found on the cell surface of all nucleated cells in the bodies of vertebrates, as well as platelets, but not on red blood cells.

MHC class II molecule: the main function of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules is to present processed antigens (normally found on dendritic cells)

Monocyte: the source of other vital elements of the immune system, such as macrophages and dendritic cells

Natural Killer Cells (NK cell or NK-LGL): A type of white blood cell that has granules (small particles) with enzymes that can kill infected cells.

Neutrophils: A type of white blood cell that helps heal damaged tissues

Pathogen: a microorganism that can cause disease